Projects

Investigating drivers’ attention in manual and autonomous vehicles.

This project is sponsored by Berkeley Deep Drive.

The recent advent of autonomous vehicles (AVs) in the last decade has changed the traditional role of drivers, from being fully responsible of all driving functions to adopting a supervising role in an AV. As of today, AVs are not perfect systems, they may make mistakes and require the driver to take control. Drivers must then monitor the AV behaviors to ensure safety of such technology. During this year’s BDD-sponsored project, we found that drivers’ attention shifted when they were monitoring an AV compared to when they were actually driving a manual car. In particular, drivers’ attention while monitoring an AV was more distributed across the visual field.

The goal of the proposed project for this year is to investigate whether this shift in drivers’ attention in AVs comes from an increased tendency to look at driving-irrelevant or salient, distracting areas. To this purpose, we propose to use our previously developed framework comparing drivers’ gaze in a driving simulator in different degrees of car automation. If drivers in AVs are in fact spending more time looking at distracting, driving-irrelevant areas, then we can use the influence of these areas in drivers’ attention through eye movements as a measure of drivers’ awareness and distraction. A driving monitoring system could be then developed based on these findings to alert drivers to maintain attention when their level of distraction increases. Click here for the github repo.

Face similarity

In our previous work, we have shown that people perceive faces in a unique way depending on their experiences. In this project, our goal is to visualize these differences in face perception. In a reverse correlation task, we visualize participant’s face template. Then, we compare the similarity of each individual’s face template to investigate whether they’re unique to each person, or they are all similar. Our previous work suggest that they will be unique to each participants and they will be shaped by the faces each participant has seen the most during their life.

To compare face template similarity, we use normalized cross-correlation and structural similarity measures on the individual pixels of the face template and on the feature extracted maps and gram matrices of the images after passing through a trained CNN.

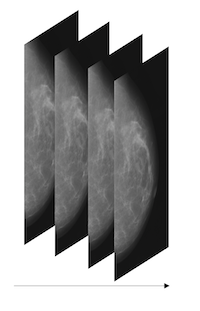

Sequential effects in radiological screening.

In radiological screening, radiologists scan myriads of radiographs with the intent of recognizing and differentiating cancerous masses. Even though they are trained experts, radiologists’ human search engines are not perfect: average daily error rates are estimated around 3-5%. A main underlying assumption in radiological screening is that visual search on a current radiograph occurs independently on previously seen radiographs. However, recent studies have shown that our current perception is biased by previously seen stimuli (Fisher & Whitney, 2014; Liberman et al., 2014); the bias in our visual system to misperceive current stimuli towards previous stimuli is called serial dependence. Here, we tested whether serial dependence impacts recognition of tumor-like shapes embedded in actual radiographs.

Foveal Selectivity in Holistic Processing of Mooney faces.

Individual Differences in Holistic Processing of Mooney Faces.

Humans perceive faces holistically rather than as a set of separate features (Sergent, 1984). Previous work demonstrates that some individuals are better at this holistic type of processing than others (Russell et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2012). Here, we show that there are unique individual differences in holistic processing of specific Mooney faces. We operationalized the increased difficulty of recognizing a face when inverted compared to upright as a measure of the degree to which individual Mooney faces were processed holistically by individual observers. Our results show that Mooney faces vary considerably in the extent to which they tap into holistic processing; some Mooney faces require holistic processing more than others. Importantly, there is little between-subject agreement about which faces are processed holistically; specific faces that are processed holistically by one observer are not by other observers. Essentially, what counts as holistic for one person is unique to that particular observer. Interestingly, we found that the per-face, per-observer differences in face discrimination only occurred for harder Mooney faces that required relatively more holistic processing. These findings suggest that holistic processing of hard Mooney faces depends on a particular observer’s experience whereas processing of easier, cartoon-like Mooney faces can proceed universally for everyone. Future work using Mooney faces in perception research should take these stimulus-specific individual differences into account to best isolate holistic processing.